In a world of fluctuating energy costs, stringent ESG targets, and equipment operating across extreme climates, kinematic viscosity is no longer just a number from a lab report. It directly dictates lubrication reliability, energy efficiency, and Total Cost of Ownership (TCO).

What is Kinematic Viscosity?

Definition: Kinematic viscosity (symbol ν) represents a fluid’s resistance to flow under gravity. It is the dynamic viscosity (μ) divided by the fluid’s density (ρ): ν = μ / ρ.

Unit: The SI unit is m²/s. In industry, the common unit is mm²/s, also known as centistokes (cSt). 1 mm²/s = 1 cSt.

Strong Temperature Dependence: Viscosity decreases significantly as temperature rises and increases significantly as it falls. Any viscosity value must be stated with its measurement temperature (e.g., 46 cSt at 40°C).

Conversion from Dynamic Viscosity: A common relationship is: cSt = cP / Density (g/cm³)

Example: If an oil has a dynamic viscosity μ = 100 cP and a density = 0.86 g/cm³ at 40°C, its kinematic viscosity ν is approximately 100 / 0.86 = 116.3 cSt.

Related Metrics:

Viscosity Index (VI, ASTM D2270): Calculated from the kinematic viscosities at 40°C and 100°C, VI indicates the “stability” of viscosity with temperature changes. A higher VI means greater resistance to temperature-induced viscosity change.

HTHS (High-Temperature High-Shear) Viscosity: Commonly used for engines and high-shear applications, HTHS complements kinematic viscosity but is measured under different conditions.

How Kinematic Viscosity Impacts Lubrication & Efficiency

Kinematic viscosity acts as a delicate balance between protection and efficiency. Both excessively low and high viscosity can cause problems.

1. Oil Film and Wear Control

Higher viscosity and speed facilitate the formation of a thicker lubricating film, reducing the risk of metal-to-metal contact and adhesive wear.

Viscosity that is too low can lead to boundary lubrication (high friction, high wear), while an appropriate viscosity can achieve hydrodynamic/elastohydrodynamic lubrication (low friction, low wear).

At high temperatures, viscosity drops and the oil film thins, requiring a sufficient base viscosity and a high VI to maintain protection.

2. Energy Consumption and System Response

Excessively high viscosity significantly increases churning resistance and heat generation in gearboxes and bearings, leading to higher energy consumption.

Hydraulic Systems: Thick oil can cause pump cavitation, increased pressure drops, and sluggish valve response. Thin oil increases internal leakage and reduces volumetric efficiency.

Cold Starts: In cold regions (e.g., Canada, Scandinavia), low temperatures cause viscosity to soar, increasing start-up load and wear risk.

Kinematic Viscosity: Climate, Industry & Global Standards

1. Climate and Geographical Differences

Cold Climates (Scandinavia, Canada): Prioritize low-temperature pumpability and high VI to reduce cold-start losses.

Hot Climates (Middle East, Africa, Southeast Asia): Focus on viscosity loss at high operating temperatures, selecting the right grade and VI to stay within the target range.

2. Industry Applications

Industrial & Mobile Hydraulics: Efficiency and responsiveness are key. Selection is often among ISO VG 32/46/68, optimized for the “actual operating oil temperature.”

Wind Power & New Energy: Large temperature swings and high shear demand excellent VI and shear stability.

Marine & Offshore: Bearings and low-speed gears require stable viscosity and water resistance; compliance with ISO/ASTM and class society recommendations is crucial.

Automotive/Heavy-duty Machinery: OEM approvals and HTHS requirements dominate. The trend towards energy conservation is pushing viscosities lower, but shear stability must be maintained.

3. Internationally Recognized Standards

Kinematic Viscosity: ASTM D445, ISO 3104

Dynamic Viscosity + Density (to calculate ν): ASTM D7042

Viscosity Index Calculation: ASTM D2270

Legacy Timed-Flow Methods (still in some older specs): Saybolt (ASTM D88), Redwood (historical British method)

How to Measure Kinematic Viscosity: Methods & Instruments

1. Capillary (Gravity) Viscometers: The Laboratory “Gold Standard”

Types: Ubbelohde, Ostwald, Cannon–Fenske, Zeitfuchs, etc.

Principle: In a constant temperature bath, the sample flows through a capillary tube under gravity. The time taken to pass between two marks is measured and multiplied by the instrument’s constant to yield the kinematic viscosity.

Standards: ASTM D445, ISO 3104, DIN 51562.

Pros: High traceability, authoritative results, widely used for lubricant inspection and QC.

Cons: Manual, labor-intensive, requires precise temperature control and rigorous cleaning, limited throughput.

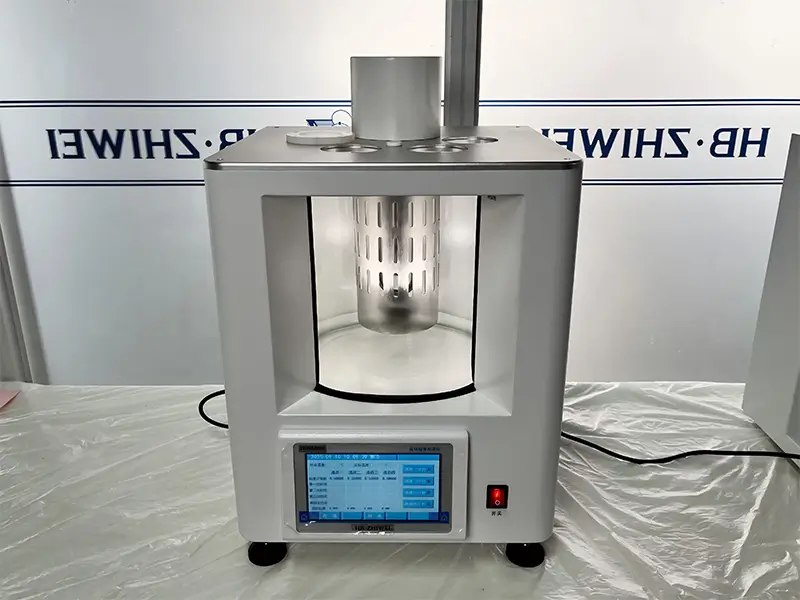

2. Automated Capillary Viscometers

Principle: Same as glass capillaries but with automated sample injection, vacuum aspiration, optical or thermal detection, and automated cleaning and temperature control.

Ideal for: High-throughput labs, oil blending plants, third-party testing services.

Pros: Excellent repeatability, saves labor, can run tests at multiple temperatures simultaneously (e.g., 40°C and 100°C).

Note: Still a gravity-based method compliant with D445. Selection depends on bath capacity, temperature stability, detection method, and cleaning efficiency.

3. Falling/Rolling Ball Viscometers (for Micro-Samples)

Principle: A sphere rolls or falls through a fluid in an inclined tube; the time is related to viscosity.

Often measures dynamic viscosity (μ); requires density data to convert to kinematic viscosity.

Pros: Requires a very small sample volume, ideal for expensive or rare fluids.

Cons: Not ideal for multiphase or non-Newtonian samples; requires density for conversion.

4. Rotational/Vibrational Viscometers (Common for Process/Field Use)

Rotational (coaxial cylinder, cone-and-plate, paddle) and vibrational (oscillating piston/resonant probe) viscometers primarily measure dynamic viscosity.

If density is measured simultaneously (online or offline), kinematic viscosity can be calculated.

Standards & Methods: e.g., ASTM D7042 (Stabinger method), which measures dynamic viscosity and density concurrently to calculate kinematic viscosity.

Pros: Fast response, suitable for online monitoring and process control; can be used for non-Newtonian fluids.

Cons: Fundamentally measures μ, instrumentation and calibration are more complex, and conversion to ν requires accurate density.

5. Saybolt/Redwood Timed-Flow Methods (Legacy)

The Saybolt (ASTM D88) and Redwood (traditional British) methods measure the time it takes for a fluid to flow through a specific orifice, yielding a result in “seconds,” which is then converted to cSt using a formula.

Now primarily used for legacy specifications or specific industry comparisons; standard labs have widely adopted ASTM D445.

6. Online Process Viscometers & System Integration

Applications: Blending control, online viscosity control of fuel and lubricating oils, condition monitoring of circulating systems.

Solution: A dynamic viscosity probe combined with an online density meter (or a temperature-density model) and temperature compensation to calculate and output kinematic viscosity in real-time.

Pros: Real-time data, enables closed-loop control, reduces offline testing frequency.

Note: Requires careful management of sensor cleanliness, vibration resistance, and bubble prevention; calibration strategy must match the process.

7. Portable Field Viscometers

Suitable for rapid trend monitoring and screening for oil degradation (e.g., fuel dilution, oxidation thickening).

Often provide relative or approximate values; used to decide whether to send a sample for lab analysis or change the oil, not as a substitute for a standard report.

Practical Tips for Reliable Data

1. Always Report Viscosity with Temperature: e.g., “68.5 cSt at 40°C”.

2. Ensure Thermal Equilibrium: Allow samples sufficient time to reach the set temperature and for air bubbles to dissipate.

3. Cleanliness is Key: Residue in glassware or instrument tubing will significantly affect flow time.

4. μ→ν Conversion: Density must be measured at the same temperature as viscosity (e.g., per ASTM D4052).

5. Multi-grade & Polymer-Modified Oils: Be aware of shear thinning under high shear; HTHS and long-term stability can sometimes be more predictive.

6. Non-Newtonian Fluids: Readings may differ between measurement methods. Most lubricants are near-Newtonian, but oils with VI improvers can show variation under high shear.

Viscosity Guidelines by Equipment Type

Rolling Element Bearings: The goal is to achieve a viscosity of typically 15–30 cSt at the bearing’s operating temperature (an empirical range, depending on DN value and load) to form an adequate oil film without excessive churning.

Hydraulic Systems: A common recommendation is to maintain viscosity between 10–100 cSt at operating temperature, with many OEMs preferring an optimal range of 16–36 cSt to balance low leakage with good responsiveness.

Gearboxes: Heavy-duty, low-speed gears (like worm gears) often require higher viscosity to maintain the oil film. High-speed gears need lower viscosity to reduce churning losses. Selection depends on the gear ratio, load, temperature, and housing design.

Engines: Beyond base viscosity, High-Temperature High-Shear (HTHS) viscosity is critical. It directly relates to the oil film’s ability to support loads and reduce friction at 150°C under high shear. A low HTHS aids fuel economy but may increase wear; always follow OEM specifications.

FAQ of Kinematic Viscosity

1. Are kinematic and dynamic viscosity the same thing?

No. Kinematic viscosity (ν, in cSt) = Dynamic viscosity (μ, in cP) / Density (in g/cm³). The conversion must be done at the same temperature.

2. Why are 40°C and 100°C the common test temperatures?

These two reference points allow for easy comparison across different oils and are used to calculate the Viscosity Index (VI). Paired with the actual operating temperature, they help predict in-service performance.

3. Can I get kinematic viscosity (ν) directly from a rotational or vibrational viscometer?

These instruments typically measure dynamic viscosity (μ). If you can obtain the density at the same temperature, you can calculate ν. For compliance reporting, you must follow the specified method (often ASTM D445/ISO 3104 or D7042).

4. How can different labs ensure consistent results?

By using traceable standard reference oils, adhering to the same standard methods, precisely controlling temperature, and participating in inter-laboratory cross-check programs. For critical applications, following a quality system like ISO/IEC 17025 is recommended.

5. Does a higher viscosity always mean better protection?

Not necessarily. Excessively high viscosity increases churning and pumping losses, heat generation, and start-up load. The correct approach is to select a lubricant that falls within the optimal viscosity range at its operating temperature, balancing oil film strength with energy efficiency.

Putting Viscosity Management into Practice: A Checklist for Better Lubrication & Efficiency

Create a “Temperature-Viscosity Profile”: For critical assets, record actual operating oil temperatures and map them to their corresponding viscosity ranges and energy consumption curves.

Establish Monitoring Frequencies: Increase viscosity testing frequency for new equipment or after process changes. For stable operations, monitor quarterly or semi-annually and compare at the same temperature.

Focus on Trends, Not Single Points: A gradual increase or decrease in viscosity is more informative. Correlate it with water content, acid number, and wear debris analysis to identify the root cause.

Optimize System Temperature: Oil temperature is the “dial” for viscosity and energy use. Proper cooling and insulation can keep viscosity in its optimal zone.

Discover Our Advanced Lubrication Solutions

Extend equipment life and reduce maintenance costs.

Optimize energy efficiency and cut operational expenses.

Ensure reliable performance under extreme conditions.

Access customized expert consultation services.

From theory to practice, from challenge to excellence—your journey to enhanced equipment performance starts now! Contact us today or explore our products and services.